From idea-bearing form to released sculpture

By Geir Uthaug

Men are crystals for our minds

– Novalis

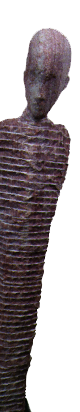

Sculpture belongs to the oldest artforms known to man. The small fertility- goddess known by the name of Venus from Willendorf is from the Paleolitic age. Later on sculptures became taller and slimmer and civilization-bearing. They formed images of pharaoes, gods and goddesses, they became mythical figures, servants of the temples, and guardians of secrets. Fredrik KB’s sculptures carries associations to primeval images from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. The stone forms layer upon layer, cut into the rock like ribbons, or glittering in crystal-shimmering quarts.

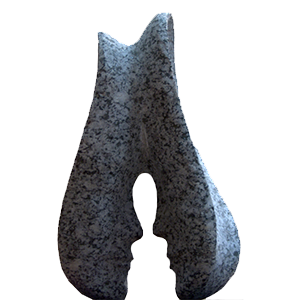

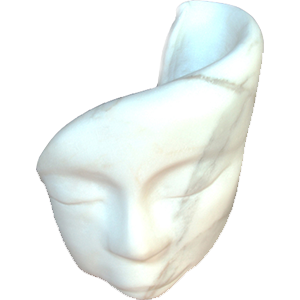

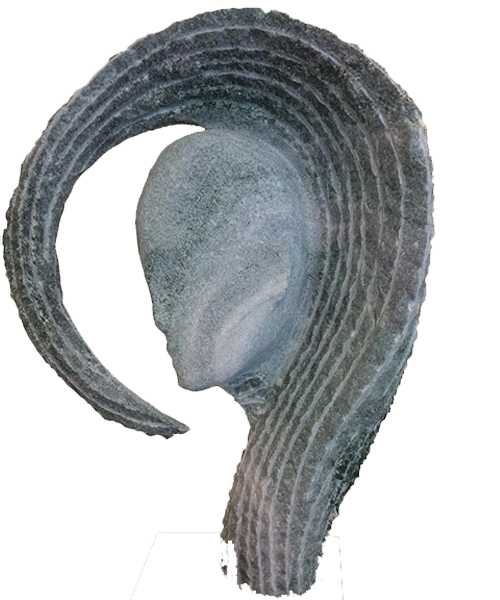

The heads have something of an enigmatic unfathomable air about them, more universal than individual, even though they retain their unique characteristics, and often denote mental states: silent they may be, and yet they speak to the imaginative aspects of our being: Women carved out of solid bedrock achieve a strange softness, they have graceful shapes, as if they are flesh and blood, draped in transparent robes. After having received a solid turn from the hammer and chisel, the stone seems to lose its weight, achieving an etheric lightness. Faces peer at us through gossamer-like veils deep into the rock, as if the human being inside is trapped and wants to get out. The illusion is magical, but tangible, for it may be touched and felt. For even though we may play around with literary associations and optical phenomena absorbed mentally, Fredrik’s sculptures are not abstractions, they are not even abstract, but highly concrete. They are images hewn from the rock. They are incarnated from mother earth, from matter herself. The heaviest and most solid of all.

In mythology and fairy-tales stones carry great significance. The images we may find are numerous: Women who were turned into pillars of salt when they stopped to gaze in the direction of the burning cities which were pelted by meteors; the ogres who were petrified as the sun rose. But stone can also become flesh and blood. Matter may be given life, as when the earth-man Adam was animated by the the breath of life. Did not the Norwegian romantic poet Henrik Wergeland (who loved crystals and stones) write that the clear gem may burn in the dark?

One of Fredrik’s favourite stories is the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea which tells of the sculptor who had carved a woman from a slab of marble. He fashions the female form so beautifully that he falls in love with her, and so great is his love that the goddess of love, Aphrodite, feels pity for him and makes her come alive.

Fredrik was drawn towards the Mecca of sculptors, the marble quarry of Carrara in Tuscany. It was a calling preceded by omens and dreams. The story of how he at his arrival went to seek for a master, and in the end just started to cut the marble to make his first little sculpture whom he named Albert and vowed never to part with, is part of his story, but it is a story he likes to share, for it tells a lot about the enthusiasm and dedication which is his driving force.

What must be present in a man in order to create? Which forces are at work in order to gouge images out of matter? The English philosopher and poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge has described it in the following terms: There are two creative forces at work in an artist. The first is a gift which has been given to everybody, this is where the idea incarnates in the mind, or if we like, where imagination opens reality to us, as when we absorb a glorious sunrise; but if the imagination shall able to undergo a transformation and become something concrete, like a work of art, another force is necessary, it is that which, as it were, takes hold of the impression and bends it inwards, does something about it, so that the creative process is allowed to take place. This is the explanation of the mystic; the great painter J.M.W. Turner put it more sober terms: “I know of no genius but the genius of hard work.”

Fredrik knows from his own experience that both are right, but for an artist who works with stone, hard work is impossible to bypass. In the dramatic poem ”Peer Gynt” Ibsen talks about the force he calls the Bøyg, who always bids Peer to step around things, to avoid the real challenges in life; but to an artist who works with stone no Bøyg is formidable enough to ask him to step aside. It is heavy work too, strenuous and timeconsuming.

It has nothing glamorous about it, but it is here he approaches what William Blake, a poet-artist who has meant a lot to Fredrik, calls the forge of creativity. For an artist this is something resembling happiness. It is a big gap between the presentation of sculptures in the setting of a stylish art gallery, and the surroundings where the sculptures are made. It is nothing polished about his workshop. It is a remote place, the setting is simple but recognizable: it is an open space with big machines for cutting and drilling, strewn with piles of rock; there are storing rooms and warehouses, and workshops with even more machinery. He is enveloped in noise and dust, there are stonemasons working in groups, who know their trade from a practical side, which is so important in order to make anything at all from stone; be it tombstones or artefacts or – as in Fredrik’s case – exquisite sculptures. There are other sculptors here too, good colleagues and workmates. It is the old idea of the place where artists can commune and work together, known from both Titian’s workshop as from Shakespeare’s Fisher’s Folly.

Fredrik has his own shack in the corner of one of the buildings. A simple makeshift roof provides shelter from the rain and the snow; the wind often blows right through or past the few pillars which uphold the roof. Here, almost in the open air, his sculptures are made, some of which are already finished and are sitting in the shadows ready to be transported out into the world on large trucks; others are half-done, others still are just slabs of stone as yet, with rudimentary scars and holes drilled in them. A row of small stones is lining the top of a brick wall. Fredrik surveys them, touches them, considers their possibilities. Here anything may happen, here the images are waiting to be born.

Every sculpture he fashions has its own individuality. There is nothing mechanical about them, these are not industrial products. He makes dancing torsos, he captures the lineaments of gods, sages and dragons.

They are earthly or winged forms. They belong to multiple dimensions. The Greeks of old spoke of techné and techné mousiké. Both so important to give the artwork form and expression. The first denotes the craft itself, the handiwork, which craves its man – but the other is the definitive leap from handicraft to what we call art, which cannot really be defined, not art as a concept, but the idea-bearing form. What did Michelangelo say? To create sculpture is simple – all that it necessary is to remove the superfluous.

Art is today a concept under siege. So many vessels may be filled with contents which goes by the name of art. Art is produced on screens assisted by all kinds of facilities and optical techniques, which creates a deep chasm between art and craft. Fredrik is an artist who prefers the old traditions. Where the hammer is an extension of the mason’s arm.

Where the craft, as it were, can be felt in the body, and the execution protrudes to the fingertips. He has not pursued the academic way, for when he applied at the Oslo Academy of art, they had shut down the class for stone sculpture, instead he was taught by other stone masons and sculptors, he acquired the necessary skill which is his heritage from the time when he for some unexplained reason was drawn to Pietrasanta and Carrara and an old stone sculptor gave him his set of tools as a sign that he was considered worthy. It was a gift which carried a great responsibility, like an oath. It meant that he vowed to take up and develop the old trade so that it would retain its forceful impact and be conveyed to new generations.

The craft of art-masonry is a physical craft. Rough and sensually so. It demands muscles, a clear mind, a warm heart, a skilful hand and a boundless patience. It entails both action and meditation. It also demands a sharp eye and a gift for calculation. It is all about carving and hueing in stone, making choices among slabs of stone, discover possibilities hidden in the mountain ores, in the grooves and dents and flats. Something of the roughness, the coarseness, the primeval will be retained, other parts need to be brightly polished in order to constitute a contrast to the roughness and rustic quality of the stone. This means that it is necessary to get to know the qualities imbedded in the stone itself, to entice from it what is already present – what is possible to achieve with one species of stone is impossible with another. Knowledge of how to cleave bits of rock into sizable stones is necessary, this is achieved by driving wedges into the rock using hammers.

When this challenging work is done, the most difficult task remains – to fashion the stone, using a selection of chisels in various grades of thickness and sharpness. Fredrik explains that this may be compared to a golfer choosing the right club among all the other clubs he has in his collection. Each club has been fashioned in a special way, the angle and curve vary according to the necessary length, angle and force of thrust. In the same way the stonemason must consider his tool, which is of the utmost importance. Then the trick is to work the stone which gradually reveals its inherent forms. Unfinished fragments from the quarries carry the fulfilment.

It is also about geology. Stone is a science. The various types of stones are many. Each species has its qualities which takes time to get to know. But it is impossible to work with stones without obtaining an intimate contact. Finding the analogies presents no problems for Fredrik. In the myths natural forces are often seen as females. Just think of the hymadryads in Greek mythology, the female beings who inhabit trees. But their sisters undoubtedly inhabit the stones. Marble was his first love. This was were it all started, with the marble quarries at Carrara. Later he added granite, the primeval Norwegian rock, for even though Fredrik is a cosmopolitan who has his base in Haarlem, outside Amsterdam, he is drawn to Norway, where his workshop is.

There are many beautiful types of stone in Norway. A favourite of his is a species called “Larvikite”, which, as the name suggests, is developed in the area around Larvik near the Oslo fiord. And from thence it is exported to many countries around the world. It comes in many forms. One is the profoundly black type with blue crystals, also called Emerald Pearl, and the brown one which can contain crystals in all the colours of the rainbow. Fredrik explains: “It is also called Antique and is one of my favourites. The brown one is gentler, the black type is more masculine, and is reflected in the way I work. Then comes the fantastic Wasa, or Älvdals-granite, which has layers in red and white, sometimes transforming a face into a topographical map. Then we have the green, crazy and headstrong Masi-quartzite from Kautokeino. It has hard, beautiful, white ores and soft ores of shimmering dark green. The green parts are like mica, and if an ore runs right through the sculpture, I have to use the smallest chisels I have. To break a stone in half is easily done. Masi helps me to stay alert. For every time I fail and try to convince myself that I know what I am doing, the beautiful lady from the far North of Norway smiles and breaks in half, and then I have to look for the lines to see where they are. She is a real loving mistress.”

The tools are of the utmost importance. He has hammers of different weight, for various purposes. Chisels are almost as personal as hammers, he explains, but they wear off more easily and must be sharpened more often.

The tools he uses cover a wide range, from air-compression-hammers driven by compressor to the minutest diamond drills, used for surgical operations, which he is able to acquire when they are discarded from the operation theatres. With the chisel he is able to cut loose large pieces at one blow of the hammer, but only if he has a straight or level side at his disposal, he can then cut through a slab by driving the chisel along a straight line alongside the stone. The blow of the hammer creates a crack which cuts many centimetres down into the slab. By fashioning this with a skilled hand, it can be more effective than an angle grinder.

It is in the energy-field between an outer and inner reality that art is born. Like other artists Fredrik has his models – Michelangelo naturally, the greatest sculptor of all, one may wonder whether it was he who called him to Carrara in the first place, and taught him to appreciate the energies there – but most important are the examples he can find in his own inner being. His search may be for something lost, what is needed is to rediscover the means of how to obtain it.

Intimacy, spirituality, the longing for eternity, are words which spring to mind when contemplating Fredrik’s sculptures. He is on the look-out for myths and ancient imagery.

Myths open up, they are just as Blake imagined them to be, not literary associations, but spiritual realities which reveal themselves to our imagination. It is the task of the artist to open the windows of our mind, so that perception can grasp reality and recapture it in its rich orchestration.

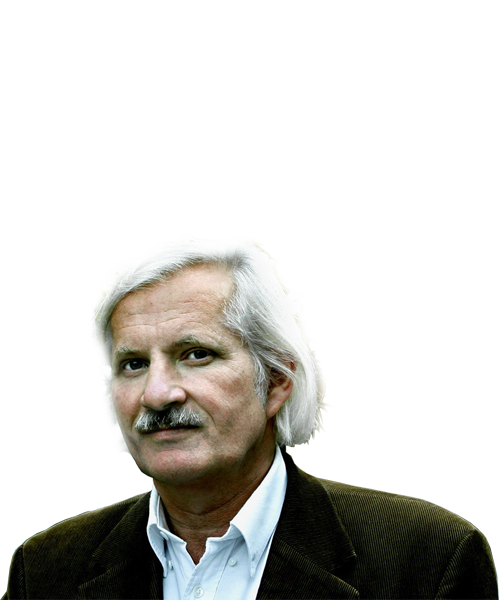

Geir Uthaug is a Norwegian writer, poet and translator and the author of a book on William Blake called “The Cosmic Forge” which has become a cult-book in Norway.

“What are those golden builders doing?” Blake asks. They are helping to construct Golgooza, the eternal City of Art, and some artists, who are conscious of their task, contribute to build it in their own minds, and fashion it in stone; for it is all about the mental city which is always threatened by deterioration, and will always have to overcome this decline, if it is to be a bulwark against formlessness. “Truth is beauty, beauty truth,“ John Keats wrote. Eternity-longing beauty is embedded in Fredrik KB’s sculptures like a form-rendering idea which in its redeemed form can overcome the limitations of matter.

For Fredrik, as for Blake, the outline constitutes the border between creation and chaos. Fredrik works in the three-dimensional, but also the linear; it is all about sharpness versus softness, that which defines the limits, and that which opens up. Something of the essence of an artwork which is created is the use of symbolic imagery, which does not need to be as explicit as in the written language. There it must be pointed and made manifest, but when it comes to sculpture, the innuendo is adequate, nay, mandatory. No comment is required, for the sculpture is its own comment. If that is to be achieved, then more than training is needed, this is where that which cannot be expressed comes in, for which we have no words. The most difficult of all.